Informing everyone that Monk is now on Netflix and it isn’t shite.

Tag Archives: San Francisco

Point Blank (1967). How fabulous this is.

Lee Marvin had a bonkers year in 1967, this thriller and The Dirty Dozen representing the peak of his cult, not that your random audience member knew it at the time. They are a curious twosome as Point Blank appears a blueprint for a future style of film aesthetics and the Robert Aldrich ripper a throwback or definition of the classical form, if not in its then-graphic onscreen violence. It’s a watershed 52 weeks. I wasn’t alive back then, and thank fuck. But it looks eventful (just watch The Graduate).

What a seductive picture, and even the jarring time jumps work to reinforce the dreamy atmosphere of the film. The precise framing and use of colour, it LOOKS AMAZING (CAPS LOCK ALERT). The overlapping sound is pre-Robert Altman but betters those seminal works because it’s more than a silly afterthought or accident. There are scenes in this which require so little dialogue they may as well be Godard in a traffic jam. It’s an exercise in stylistics. You get this with first-time filmmakers or those in the early throes of the game – the bold choices, the going with the instinct. Peckinpah retained it almost to the end. Scorsese – the last man standing – still has it.

This is peak Tarantinto three decades before peak Tarantino. But without the feet obsession.

It’s also hilarious. Marvin has to be the coolest bloke to ever be off his tits. He retains throughout a semi-plastered hangdog expression and even in his quietest rage barely looks interested in proceedings. It’s all too easy for Marvin. All he wants is his cash but not even the corporate pyramid semi-responsible for his fate are even capable of doing the basics. Almost everyone in this movie is useless. It’s a life lesson.

Point Blank is a relic and a template.

P.S. There is no relation between this and Point Break (1991), which I watched a few weeks ago.

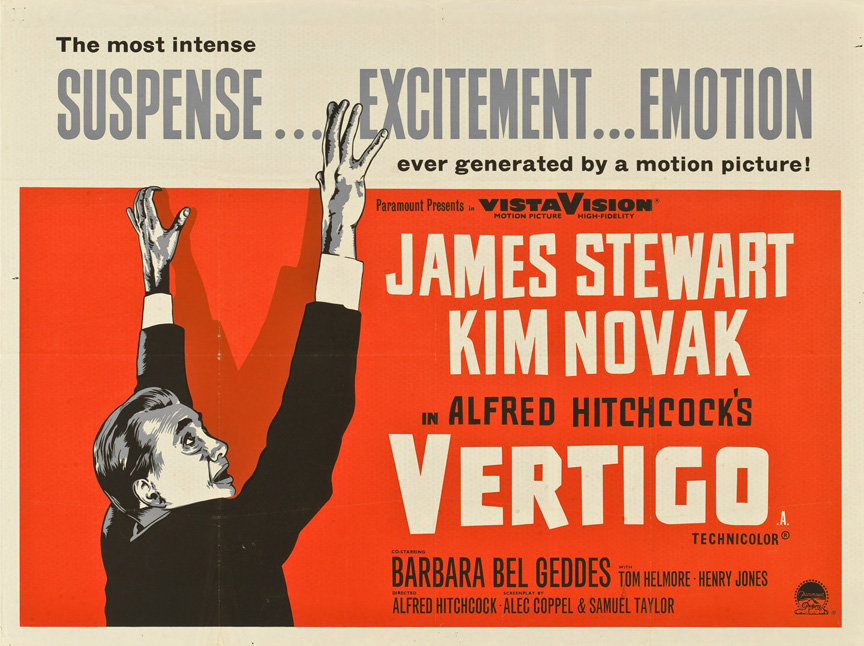

Vertigo (1958) – a whirlpool of obsession.

I first saw the unfathomable sensations of Vertigo (1958) on Boxing Day in 2001. I figured Hitchcock this go-to guy for cheap thrills, banal comedic interludes, nonsensical MacGuffins, crop dusters galore, and … trains. Vertigo spoke artistry, something deep and profound (so I heard) from the psyche. Looking at the physiognomy of the great master, one couldn’t help but think he’d spent a career pulling his plonker to his leading ladies; sources inform us, however, that he was no Mr. Miramax.

It’s a deeply unsettling picture, a compendium, in that Mad Men era, of the ‘Male Gaze‘. Novak’s ice-cold beauty is a kaleidoscope onto which John “Scottie” Ferguson projects his hysteria. She’s barely a character, and that’s the point.

A mastery of pacing, understatement, camera placement, and the semiotics of colour, the movie is your psychoanalyst’s wet dream. A narrative so stilted and sedate just builds and builds, unearthing an unblinkered aggression in every facet of the frame. It helps that the most serenely pacific of cities, San Francisco, acts as the melting pot for James Stewart’s warped solipsistic frenzy.

You watch Vertigo and witness every cinematic trope of the 50 years that followed. No Vertigo, no Brian De Palma. In 2012, Sight and Sound magazine voted Vertigo the greatest film ever made. It’s certainly more engaging than Grown Ups 2 (2013).

Further reading/viewing:

http://www.openculture.com/2016/09/what-makes-vertigo-the-best-film-of-all-time.html

https://www.theguardian.com/film/1999/mar/05/martinscorsese

http://theconversation.com/explainer-what-does-the-male-gaze-mean-and-what-about-a-female-gaze-52486

Scorsese on Vertigo: